By

Jerry Coyne

[GB:

Via "The Conversation" and its Creative Commons policy, I reprint

this interesting article

by Jerry Coyne, who summarizes his point of view on the science/religion

debate. As readers may know, I don't entirely agree with Jerry's "Fact vs.

Faith" dichotomy. As scientists, we rely on faith all the time. For

instance, we have the faith (or assumption) that "there are physical

causes for all effects". We could not prove that completely until we

discover all the causes for all effects, which is impossible. Nonetheless,

there is not a single instance in which that assumption

has failed. Of course, there is a dichotomy, but it is between determinism and

indeterminism, based on opposed assumptions as I put forth in "The Ten

Assumptions of Science." Some folks claim that this necessity to have “faith

in science” makes science a religion. That is false, because religion assumes

there is a god and science does not.]

Yes, there is a war between science and religion

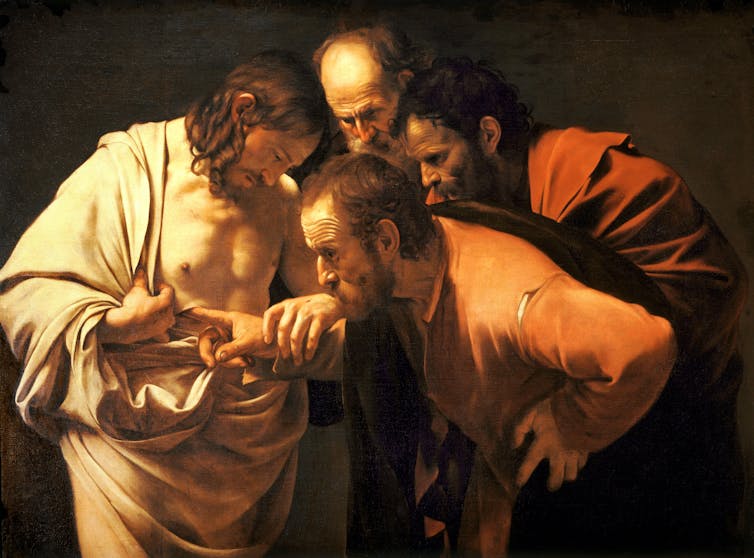

Doubting Thomas needed the proof, just

like a scientist, and now is a cautionary Biblical example.

As

the West becomes more

and more secular, and the discoveries of evolutionary biology and

cosmology shrink the boundaries of faith, the claims that science and religion

are compatible grow louder. If you’re a believer who doesn’t want to seem

anti-science, what can you do? You must argue that your faith – or any faith –

is perfectly compatible with science.

And

so one sees claim after claim from believers,

religious

scientists, prestigious

science organizations and even

atheists asserting not only that science and religion are compatible,

but also that they can actually help each other. This claim is called “accommodationism.”

But

I argue that this is misguided: that science and religion are not only in

conflict – even at “war” – but also represent incompatible ways of viewing the

world.

Opposing methods for discerning truth

The scientific method relies on observing, testing

and replication to learn about the world.

My

argument runs like this. I’ll construe “science” as the set of tools we use to

find truth about the universe, with the understanding that these truths are

provisional rather than absolute. These tools include observing nature, framing

and testing hypotheses, trying your hardest to prove that your hypothesis is

wrong to test your confidence that it’s right, doing experiments and above all

replicating your and others’ results to increase confidence in your

inference.

And

I’ll define religion as

does philosopher Daniel Dennett: “Social systems whose participants

avow belief in a supernatural agent or agents whose approval is to be sought.”

Of course many religions don’t fit that definition, but the ones whose

compatibility with science is touted most often – the Abrahamic faiths of

Judaism, Christianity and Islam – fill the bill.

Next,

realize that both religion and science rest on “truth statements” about the

universe – claims about reality. The edifice of religion differs from science by

additionally dealing with morality, purpose and meaning, but even those areas

rest on a foundation of empirical claims. You can hardly call yourself a

Christian if you don’t believe in the Resurrection of Christ, a Muslim if you

don’t believe the angel Gabriel dictated the Qur’an to Muhammad, or a Mormon if

you don’t believe that the angel Moroni showed Joseph Smith the golden plates

that became the Book of Mormon. After all, why accept a faith’s authoritative

teachings if you reject its truth claims?

Indeed,

even

the Bible notes this: “But if there be no resurrection of the dead,

then is Christ not risen: And if Christ be not risen, then is our preaching vain,

and your faith is also vain.”

Many

theologians emphasize religion’s empirical foundations, agreeing with the

physicist and Anglican priest John

Polkinghorne:

“The

question of truth is as central to [religion’s] concern as it is in science.

Religious belief can guide one in life or strengthen one at the approach of

death, but unless it is actually true it can do neither of these things and so

would amount to no more than an illusory exercise in comforting

fantasy.”

The

conflict between science and faith, then, rests on the methods they use to

decide what is true, and what truths result: These are conflicts of both

methodology and outcome.

In

contrast to the methods of science, religion adjudicates truth not empirically,

but via dogma, scripture and authority – in other words, through faith, defined

in Hebrews 11 as “the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of

things not seen.” In science, faith without evidence is a vice, while in

religion it’s a virtue. Recall what

Jesus said to “doubting Thomas,” who insisted in poking his fingers

into the resurrected Savior’s wounds: “Thomas, because thou hast seen me, thou

hast believed: blessed are they that have not seen, and yet have believed.”

Two ways to look at the same thing, never the

twain shall meet.

And

yet, without supporting evidence, Americans

believe a number of religious claims: 74 percent of us believe in

God, 68 percent in the divinity of Jesus, 68 percent in Heaven, 57 percent in

the virgin birth, and 58 percent in the Devil and Hell. Why do they think these

are true? Faith.

But

different religions make different – and often conflicting – claims, and

there’s no way to judge which claims are right. There are over 4,000 religions on this

planet, and their “truths” are quite different. (Muslims and Jews,

for instance, absolutely reject the Christian belief that Jesus was the son of

God.) Indeed, new sects often arise when some believers reject what others see

as true. Lutherans

split over the truth of evolution, while Unitarians rejected other

Protestants’ belief that

Jesus was part of God.

And

while science has had success after success in understanding the universe, the

“method” of using faith has led to no proof of the divine. How many gods are

there? What are their natures and moral creeds? Is there an afterlife? Why is

there moral and physical evil? There is no one answer to any of these

questions. All is mystery, for all rests on faith.

The

“war” between science and religion, then, is a conflict about whether you have

good reasons for believing what you do: whether you see faith as a vice or a

virtue.

Compartmentalizing realms is irrational

So

how do the faithful reconcile science and religion? Often they point to the

existence of religious scientists, like NIH

Director Francis Collins, or to the many religious people who accept

science. But I’d argue that this is compartmentalization, not compatibility,

for how can you reject the divine in your laboratory but accept that the wine you

sip on Sunday is the blood of Jesus?

Can divinity be at play in one setting but not

another?

Others

argue that in

the past religion promoted science and inspired questions about the

universe. But in the past every Westerner was religious, and it’s debatable

whether, in the long run, the progress of science has been promoted by

religion. Certainly evolutionary biology, my

own field, has been held

back strongly by creationism, which arises solely from

religion.

What

is not disputable is that today science is practiced as an atheistic discipline

– and largely by atheists. There’s a

huge disparity in religiosity between American scientists and

Americans as a whole: 64 percent of our elite scientists are atheists or

agnostics, compared to only 6 percent of the general population – more than a

tenfold difference. Whether this reflects differential attraction of

nonbelievers to science or science eroding belief – I suspect both factors

operate – the figures are prima facie evidence for a science-religion

conflict.

The

most common accommodationist argument is Stephen Jay

Gould’s thesis of “non-overlapping magisteria.” Religion and science,

he argued, don’t conflict because: “Science tries to document the factual

character of the natural world, and to develop theories that coordinate and

explain these facts. Religion, on the other hand, operates in the equally

important, but utterly different, realm of human purposes, meanings and values

– subjects that the factual domain of science might illuminate, but can never

resolve.”

This

fails on both ends. First, religion certainly makes claims about “the factual

character of the universe.” In fact, the biggest opponents of non-overlapping

magisteria are believers and theologians, many of whom reject the idea that

Abrahamic religions are “empty of any

claims to historical or scientific facts.”

Nor

is religion the sole bailiwick of “purposes, meanings and values,” which of

course differ among faiths. There’s a long and distinguished history of

philosophy and ethics – extending from Plato, Hume and Kant up to Peter Singer,

Derek Parfit and John

Rawls in our day – that relies on reason

rather than faith as a fount of morality. All serious ethical

philosophy is secular ethical philosophy.

In

the end, it’s irrational to decide what’s true in your daily life using

empirical evidence, but then rely on wishful-thinking and ancient superstitions

to judge the “truths” undergirding your faith. This leads to a mind (no matter

how scientifically renowned) at war with itself, producing the cognitive

dissonance that prompts accommodationism. If you decide to have good reasons

for holding any beliefs, then you must choose between faith and reason. And as

facts become increasingly important for the welfare of our species and our

planet, people should see faith for what it is: not a virtue but a

defect.

Jerry

Coyne, Professor Emeritus of Ecology and Evolution, University

of Chicago

This

article is republished from The

Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original

article.

No comments:

Post a Comment